Marty Tagg, Fort Huachuca Conservation Branch Chief, talks about the history of the Mountain View Officers' Club (MVOC), which served hundreds of Black soldiers who were stationed at Fort Huachuca during WWII. May 31, 2023.

Marty Tagg, Fort Huachuca Conservation Branch Chief, talks about the history of the Mountain View Officers' Club (MVOC), which served hundreds of Black soldiers who were stationed at Fort Huachuca during WWII. May 31, 2023.

The Mountain View Officers’ Club (MVOC), which served as a social club for Black officers stationed at Fort Huachuca during WWII, now has a new potential purpose as a Range Operations Synchronization Center. The Fort has submitted the proposal to the United States Army for funding in an attempt to keep the structure, and history, alive.

It’s been a decades-long struggle to find both funding and use for the building that’s more than 80 years old. Various proposals have come and gone, but none have really stuck. That is, until about two years ago when the new Deputy Garrison Commander came to Fort Huachuca’s Conservation Branch Chief Marty Tagg with an idea.

“And she said ‘you know what, the biggest issue we have at Fort Huachuca is all of our activities aren’t synchronized,’” Tagg said. “A lot of installations have Range Synchronization Centers, and if you want to know what’s going on the fort anywhere with anybody, you go to the Range Synch Center and say ‘who’s working out on this range right now?’ And they’ll say, ‘Oh these guys are’… We don’t have that … nobody knows what everybody is doing …

Our range control is in a small, falling-a-part complex, and this building is literally right across the road and the wash from the building,” he continued. “She said ‘why don’t we make this a Range Synch Center?’ And it was, like, all of us had these lightbulb moments … Because in the end, we knew that the only way we’re going to save that building was with a long-term military mission that the Army paid for.”

The Mountain View Officers' Club on Fort Huachuca, AZ. The Fort has submitted a funding proposal to rehabilitate the building as a Range Operations Synchronization Center. May 31, 2023.

The Mountain View Officers' Club on Fort Huachuca, AZ. The Fort has submitted a funding proposal to rehabilitate the building as a Range Operations Synchronization Center. May 31, 2023.

As a Range Operations Synchronization Center, the MVOC could be given a new life, but also a critical role in the Army’s mission, which Tagg said is critical for securing funding.

Sasha Romih, the Fort’s cultural resource program manager, said the center will have classrooms but keep some of the iconic features.

“There’s going to be a classroom so that range operations can do briefs with units that are coming in to do various trainings,” Romih said. “There is a plan to have the central ballroom of the MVOC become kinda like a war room … so you can have, like, a central table or something that showcases Fort Huachuca, and you could kinda have real-time screens everywhere showing what’s going on at the airfield, out on the east range, what’s going on at the firing ranges.”

She says that the plan also includes an homage to the original 1943 art exhibit, curated by Lew Davis, that was once in the MVOC.

“We put together a history report specifically on that art exhibit, and we’re trying to trace down all of that artwork so that we can get reproductions and put it back up in the building,” Romih said.

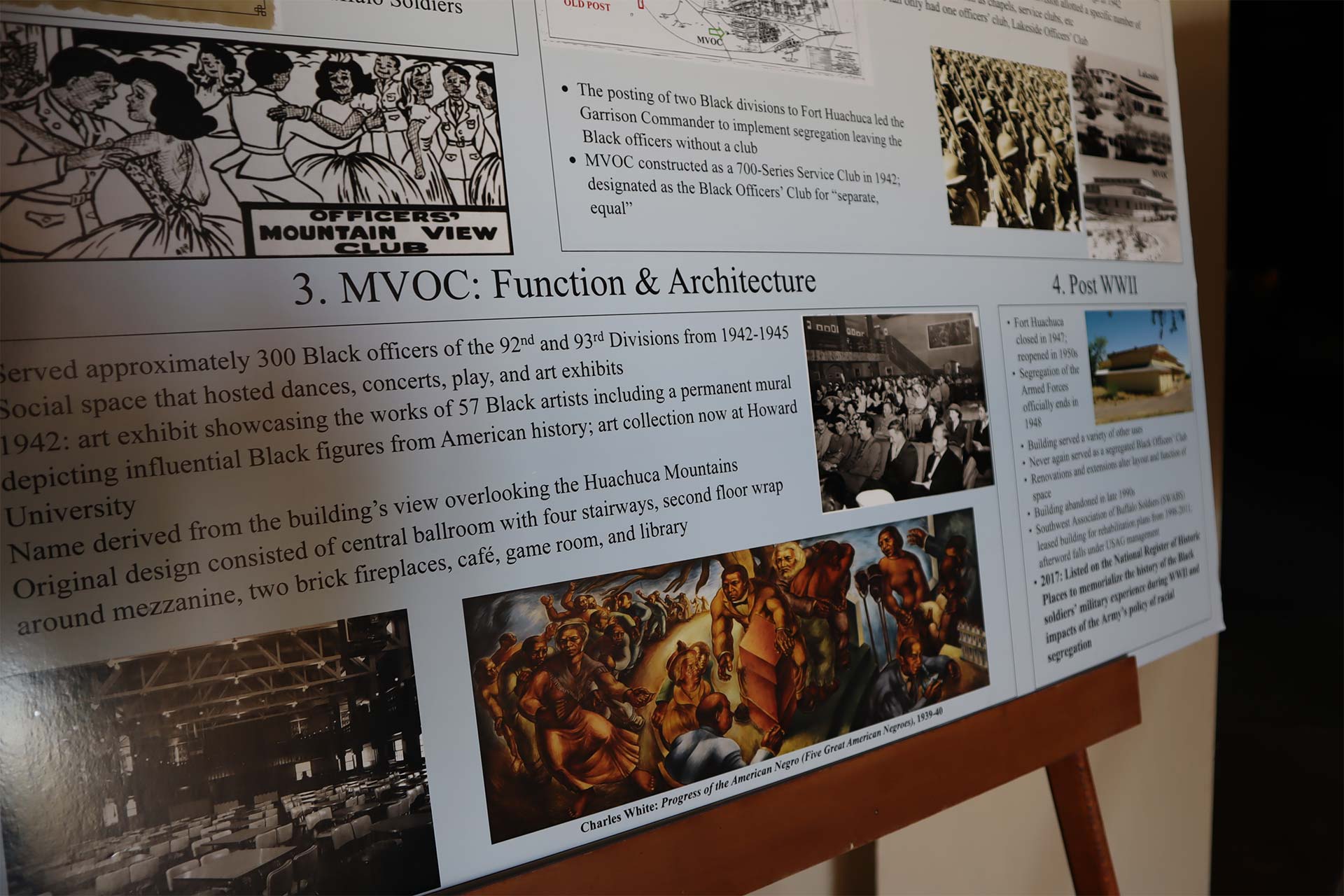

A history presentation board still stands inside the Mountain View Officers' Club. May 31, 2023.

A history presentation board still stands inside the Mountain View Officers' Club. May 31, 2023.

The funding proposal was sent to the Army in January of 2023 and officials at the fort are waiting to hear if the project and proposal will be approved. The cost of rehabilitating the MVOC as a Range Operations Synchronization Center can’t be discussed publicly yet.

But let’s backtrack. How did all of this begin?

History of the MVOC

When you hear about Black soldiers serving at Fort Huachuca, you may think of the Buffalo Soldiers, which mostly consisted of Black soldiers who had enlisted in the military during the Civil War and continued to serve afterward to fight on the frontier lands in the West during the Plain Wars with Native American Tribes according to an article from the National Parks Service.

And you may also think of the Black soldiers and civil service members who served on Fort Huachuca after the fort was reactivated in the 1950s for training and testing electronic communications equipment through the establishment of Electronic Proving Ground (EPG) in 1954 and the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence in 1971 according to the Army’s website.

But there’s a gap there.

That’s where the Mountain View Officers’ Club comes in. Built in 1942 as a Series 700 Service Club, the Mountain View Officers’ Club was a social venue for the 92nd and 93rd all-Black divisions, who were stationed at Fort Huachuca during WWII.

“They would do plays there, they would bring in famous musicians and singers and athletes,” said Tagg. “And then, they had their own Fort bands.”

“They didn’t build the fort to be segregated,” Tagg said. “They built it with a certain number of each building inside, which included one officers’ club which was Lakeside.”

But Tagg said that Fort Huachuca’s commander at the time decided to keep the fort segregated and the Lakeside Officers’ Club only permitted white officers. Thus, the Mountain View Officers’ Club was built to accommodate the hundreds of Black soldiers who arrived for training before deployment. It wasn’t until 1948 that President Harry Truman desegregated the armed forces.

But after the war, the club once filled with music, laughter, and dancing, slowly became quiet.

“Right after the war, the Fort closed,” Tagg continued. “And, they actually started removing a lot of the World War Two buildings … But this building remained.”

Tagg said the first known use of the MVOC after the war was In the 1950s when the Electronic Proving Ground or EPG established its headquarters at Fort Huachuca.

“We have photos of the MVOC as the EPG Service Club,” he said.

But as far as what happened to the MVOC between the 1950s and the 1990s, isn’t really known. Tagg said it likely was vacant most of the time with occasional events hosted here and there.

The struggle to find a purpose for the building

In 1998, the MVOC was placed on the demolition list. But the MVOC was removed from the list and instead was leased for five years to the Southwest Association of Buffalo Soldiers in 2006. But Tagg said that lease was not renewed.

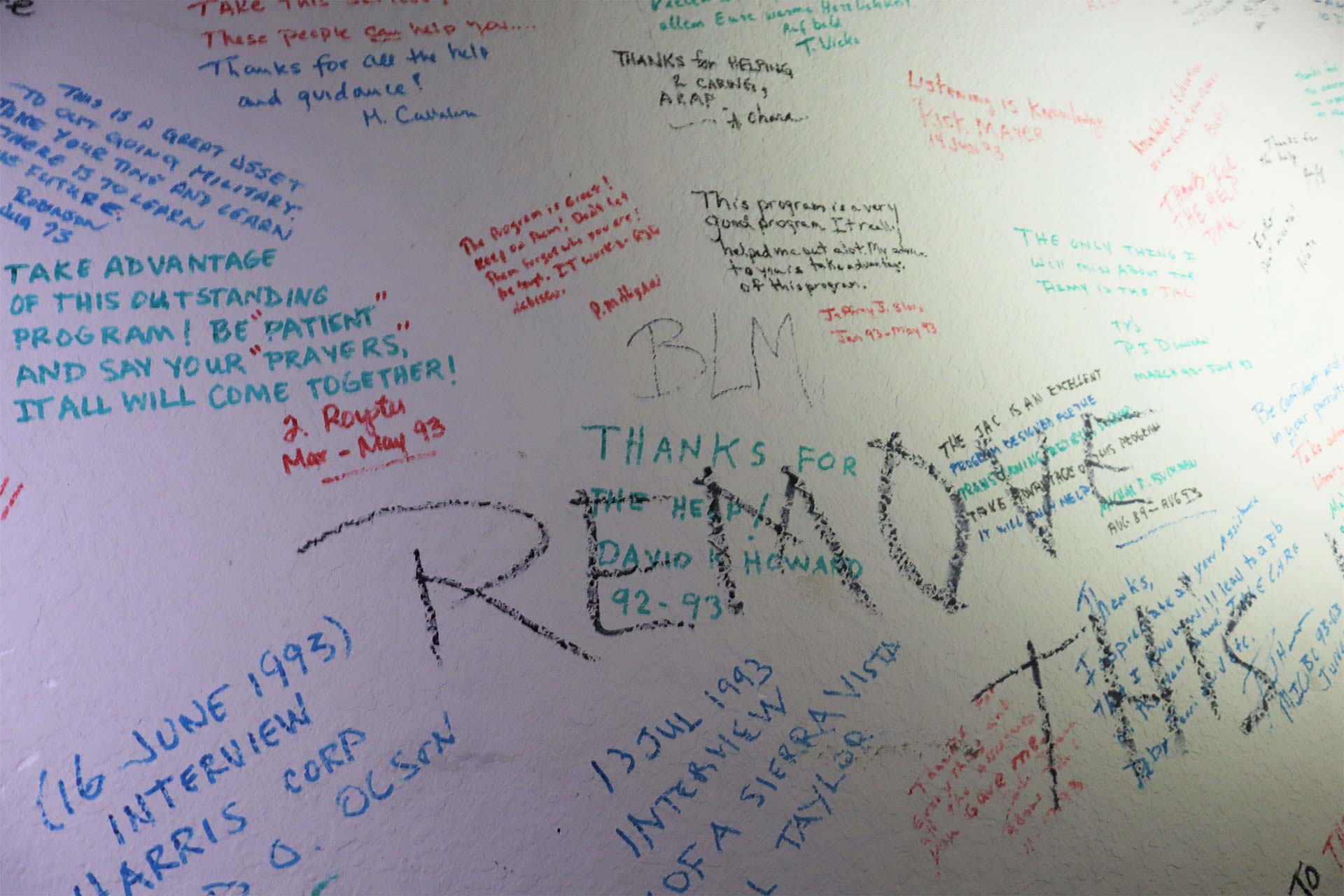

The "graffiti wall" inside the Mountain View Officers' Club. During the 1980s and early 1990s, the Army used the building as a location where soldiers leaving the service learned about getting jobs in the civilian world. Many of those soldiers left messages on the graffiti wall. May 31, 2023.

The "graffiti wall" inside the Mountain View Officers' Club. During the 1980s and early 1990s, the Army used the building as a location where soldiers leaving the service learned about getting jobs in the civilian world. Many of those soldiers left messages on the graffiti wall. May 31, 2023.

“They had a plan, they had a concept,” said Tagg. “They wanted to turn it into this Black museum cultural center. But they are a very small organization … They weren’t getting tens and thousands of dollars in donations.”

He added that one of the conditions of the lease includes addressing safety issues.

“There are a lot of safety issues, and that was one of the critical things in the lease was that they correct the safety issues,” said Tagg. “And they didn’t — which is why we didn’t renew their lease.”

Ultimately, the Army wasn’t able to find a use for the MVOC, so no further resources were delegated to it.

Inside the Mountain View Officers' Club on Fort Huachuca, AZ. May 31, 2023.

Inside the Mountain View Officers' Club on Fort Huachuca, AZ. May 31, 2023.

“We can’t just save the building if we don’t use it,” said Tagg. “And the Army has said ‘we have no use for this building.’”

But numerous attempts were made to find a purpose for the MVOC, find funding, and recognize the MVOC’s historical value. In 2017, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. But the fort still wasn’t able to find a way to secure enough funding to make the building habitable or a place within its mission.

“All of these plans … we would go down a road, and then, hit a dead end,” Tagg said.

Tagg says their options were to either (a) rehabilitate the building and use it for something else, (b) sell it, or (c) demolish it.

And that’s when the deputy garrison commander came through with an idea to turn the MVOC into a Range Operations Synchronization Center.

So far, there’s been no word on the proposal that was sent to the Army in January. But hope for extending the life of the building continues.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.