VIEW LARGER Most of Sara Lemmon’s artwork was lost, possibly in the fires that followed the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

VIEW LARGER Most of Sara Lemmon’s artwork was lost, possibly in the fires that followed the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

The Tohono O’odham call the mountain range to the north of Tucson Babad Do’ag, which means Frog Mountain. In the late 1600s, Jesuit missionary Eusebio Kino renamed it the Santa Catalinas. And two hundred years later, the first white woman climbed to the top and the mountains became known by her name – Mount Lemmon.

It’s just after sunrise up here on Mount Lemmon. At an elevation above 9,000 feet, it’s cold! You definitely want a jacket.

“I’m just going over my mental checklist here,” says Wynne Brown, looking through her backpack. “The most important thing is water and I have about a gallon. I have my emergency space blanket.”

VIEW LARGER Local author Wynne Brown on the Oracle Ridge Trail. Brown is writing a biography of Sara Plummer Lemmon, who is thought to have taken this route to the summit of the Catalinas.

VIEW LARGER Local author Wynne Brown on the Oracle Ridge Trail. Brown is writing a biography of Sara Plummer Lemmon, who is thought to have taken this route to the summit of the Catalinas. Brown is preparing to hike the Oracle Ridge Trail. The steep, 13-mile trail ends in the outskirts of the town of Oracle. She anticipates treacherous footing as the path descends 3,000 feet. “Let’s see. I have my phone. I have my notebook. I have a pen.”

She’ll need the pen. Brown is the author of several books about the Southwest. Her latest project is a biography of the 19th century botanist and artist for whom Mount Lemmon is named: Sara Plummer Lemmon.

VIEW LARGER Sara Plummer Lemmon was 33 years old when she left the East coast for health reasons. She went by sea to Panama and took a steamer up the coast to San Francisco. She knew no one in California. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

VIEW LARGER Sara Plummer Lemmon was 33 years old when she left the East coast for health reasons. She went by sea to Panama and took a steamer up the coast to San Francisco. She knew no one in California. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

“There’s just something about Sara Lemmon that grabbed me, probably seven years ago,” says Brown. “I’ve read through 1,400 pages of her handwritten letters. I just walk around Tucson with her voice in my ear.”

Today’s expedition is more of a pilgrimage than a hike, because Brown will be walking the same route that’s thought to be the one that Lemmon and her husband, John, took in 1881, to reach the summit.

“Being able to put my feet on the same trail that she walked on,” says Brown, “I mean, what a gift to be able to do this! I never hiked this trail so I’ll be looking at it through new eyes. And I’m going to try to look at it through Sara’s eyes. What would this have been like this many years ago?”

The trail starts just past the Mt. Lemmon fire station. The damage from past fires is evident all around, with charred trees dotting the landscape. There are also wildflowers just beginning to pop – yellow, daisy-like plants and white flowers in the raspberry family, penstemons and lupines. Brown says it would have looked very different when the Lemmons were here. She says John Lemmon’s letters describe maple trees.

Sara Lemmon was born in Maine, and John was from Michigan. They met in California. What brought them to Tucson?

VIEW LARGER The view from the Oracle Ridge Trail looking north. The landscape would have been much the same as what Sara Lemmon saw on her journey up the mountain, except of course Biosphere II would not have been in the background.

VIEW LARGER The view from the Oracle Ridge Trail looking north. The landscape would have been much the same as what Sara Lemmon saw on her journey up the mountain, except of course Biosphere II would not have been in the background. “There was a botanical frenzy going on in the 1870s and 80s,” explains Brown. “Everybody wanted to have a species named for them. Everybody was out just clambering up and down the hillsides and combing the streambeds for new ferns and then sending them off to the very few experts to identify."

"So because this area had never been botanized, it was very tempting. It was Sara’s idea to come and spend their honeymoon botanizing the Santa Catalinas.”

This was not your typical honeymoon destination. The train had only arrived in Tucson the year before, and there was the ongoing Apache conflict. Also, the Lemmons were not your typical explorers, says Brown. Both suffered from a host of serious health problems.

“The whole reason Sara was out West was because she couldn’t survive the Eastern climate,” explains Brown. “She kept coming down with pneumonia, bronchitis, something called catarrh, which is basically a build-up of mucus in the throat and the lungs — attractive thought! She realized that she was going to die if they had another Eastern winter.”

Sara moved to California in 1871, on her own (by steamer through Panama, stagecoach across Panama, and then a second steamer up the coast to San Francisco). She moved to Santa Barbara and later met her future husband. John Lemmon had fought for the Union during the Civil War and was captured by the Confederates. Brown says he never fully recovered his health after two years of near-starvation in the Andersonville and Florence prison camps.

VIEW LARGER The trailhead is just past the Mt. Lemmon fire station, off of Catalina Highway.

VIEW LARGER The trailhead is just past the Mt. Lemmon fire station, off of Catalina Highway. “They were both incredibly frail people,” she says.

It is hard to imagine these two rather sickly characters spending three weeks trying to climb the sheer, prickly slopes of the Catalina Mountains. There was no trail. There were impassable ravines. And, like any desert hikers, they had to carry their water. What was their equipment like?

“She wrote to her sister about her outfit,” says Brown. “She wore a deep olive green walking suit made out of broadcloth and corduroy, which had to be incredibly hot. And it was a short dress on top and then it had Turkish trousers on the bottom, and then she was wearing leather leggings, and hobnailed boots, and gloves, and a broad-brimmed hat."

"And then they were also carrying plant presses. They had water. They had some kind of bran mush. They had little rubber cups because sometimes the water was scarce and they’d have to be able squish them into a crack in the rock to get some water.”

Brown says botany wasn’t a very lucrative profession – at least not for the Lemmons.

“They were constantly trying to find ways to make money,” says Brown. “They were collecting plants and then selling the seeds, selling specimens, shipping them all over the world and getting pennies per plant. They found about 300 new species in Arizona.”

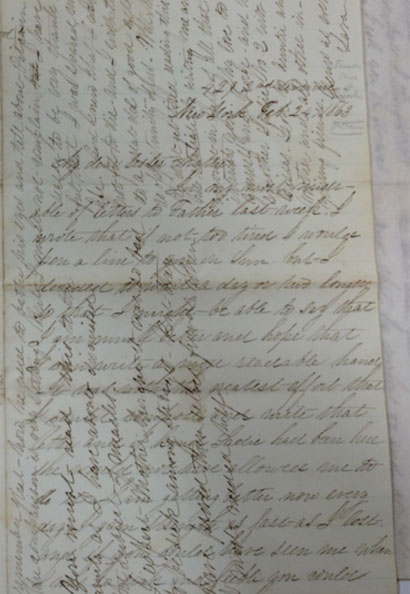

VIEW LARGER Sara Lemmon was “the frugal type,” according to biographer Wynne Brown, and to conserve paper she wrote on both sides of the page and then turned the page sideways and wrote across her own words. Brown has read transcribed, and logged 1,400 of these handwritten missives from Lemmon to her family on the East Coast. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

VIEW LARGER Sara Lemmon was “the frugal type,” according to biographer Wynne Brown, and to conserve paper she wrote on both sides of the page and then turned the page sideways and wrote across her own words. Brown has read transcribed, and logged 1,400 of these handwritten missives from Lemmon to her family on the East Coast. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

One of their finds was the mountain marigold -- “sometimes called Lemmon’s marigold,” says Brown, “named for him, not her. This was the first place where they found it. They apparently collected seeds from it. That plant from here is the stock that all the nursery plants we now get are from. And we have it in our yard. I planted it last year.”

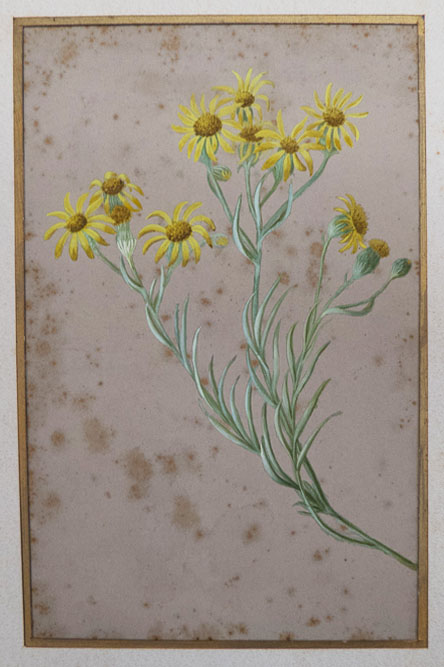

Not only was she a botanist, but Sara Lemmon was also an accomplished artist. Wynne Brown says Sara hiked with art supplies and she painted hundreds of detailed botanical illustrations, which she published in books that sold for twenty five cents a copy.

VIEW LARGER Sara Lemmon painted this watercolor of Douglass Ragwort in June 1882, at Fort Huachuca / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

VIEW LARGER Sara Lemmon painted this watercolor of Douglass Ragwort in June 1882, at Fort Huachuca / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley. “When John and Sara were up here, they were finding a lot of new species of plants,” says Brown, “and they referred to them as ‘new glories.’ And I keep finding these treasures about Sara and thinking of them, ‘Oooh! Another new glory!’ ”

For example, Sara Lemmon studied physics and chemistry at Cooper Union in New York. She was the first woman to address the California Academy of Sciences and the second woman to be admitted as a member.

“She also worked as a volunteer, nursing injured Civil War soldiers at Bellevue Hospital,” in New York, says Brown, “and that’s probably where she met Clara Barton” – the nurse who established the Red Cross. They became lifelong friends, according to Brown, and years later, Sara Lemmon helped establish Red Cross chapters in San Francisco and Oakland.

“Sara also established Santa Barbara’s first library. She helped establish the first natural history association in Santa Barbara. A new glory that I just discovered is she founded the first training school for nurses on the West Coast. She once wrote that to her sister that, to her, ‘it’s like death to be idle.’ ”

Brown says Sara Lemmon is a role model for her “because there are times when I might have wanted to quit on something and then I think, ‘I don’t have pneumonia and bronchitis, and I have all these tools, and I have the same curiosity and I try to be as resilient as she was.’ ”

VIEW LARGER Sara and John Lemmon were both avid botanists and despite their fragile health they had many outdoor adventures in the Southwest and California. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

VIEW LARGER Sara and John Lemmon were both avid botanists and despite their fragile health they had many outdoor adventures in the Southwest and California. / Photo by Wynne Brown. Original at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

After weeks of trying, Sara and John Lemmon failed to reach the summit from the Tucson side. “They gave up,” says Brown. “They were out of supplies.”

But actually, Sara didn’t give up. She and John heard that a rancher over in Oracle might know of a way up the north side. So they made the 40-mile journey to find Emerson Oliver Stratton, and he agreed to take them to the top. Sara Lemmon finally realized her dream of reaching the summit.

Stratton was distantly related to Pima County Surveyor George Roskruge, and he convinced Roskruge to put Sara’s name on the map to honor her achievement of being the first white woman to make the climb.

“What’s amazing is that Sara and John came back 25 years later to celebrate their silver wedding anniversary by doing this trip from Oracle,” says Brown (who notes that today is her one-year wedding anniversary. Her husband, Dave Peterson, is up ahead, taking pictures, and a friend has also come along on this adventure). When the Lemmons returned, they looked up Emerson Stratton, and the three of them – all in their seventies – once again hiked up to the summit. “And I hope I’m still doing that in my seventies,” says Brown.

She also hopes that Sara Lemmon’s story of grit, perseverance, and living life as a trailblazer will inspire us all.

- By Laura Markowitz, AZPM Contributing Producer

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.