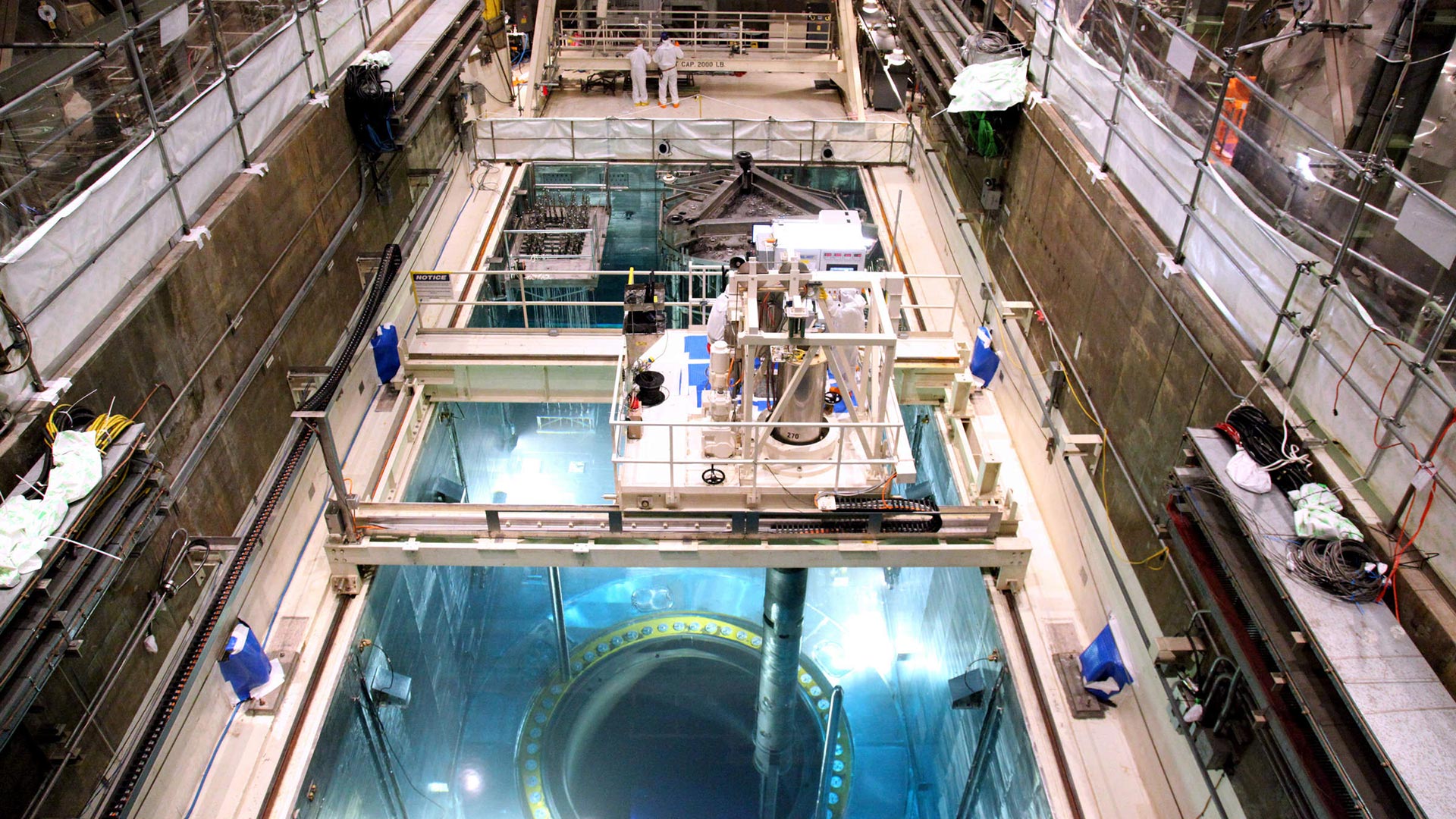

The deep blue of Cherenkov radiation reveals the location of the fuel assemblies within the open reactor core (foreground). The tube beneath the platform, a tube-shaped fuel handling machine extracts one of these assemblies.

The deep blue of Cherenkov radiation reveals the location of the fuel assemblies within the open reactor core (foreground). The tube beneath the platform, a tube-shaped fuel handling machine extracts one of these assemblies.

Every six months, Arizona’s only nuclear power plant shuts down one of its three reactors for refueling and maintenance. The Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station southwest of Phoenix recently underwent the process.

Six words greet all who enter Palo Verde - visitors, staff, or one of the thousand contractors who work around-the-clock for 30 days to refuel Unit 2: “Get your head in the game.”

But the advice extends beyond refueling, said spokesman Mark Fallon.

“It’s a huge amount of maintenance and engineering tasks that are associated with making the unit reliable for the next 18 months, once it comes back from that refueling outage,” Fallon said.

In nuclear plants, the fuel is the heat. Imagine charcoal briquettes that fire up simply by being piled together, except these “briquettes” are 8-inch-square, 14-foot-tall assemblies, composed of uranium-oxide pellets.

“A pellet about the size of the last digit of my little finger – actually, mine’s bigger than it is – is equal to a ton of coal, three barrels of oil or 17,000 cubic feet of natural gas in its energy capability,” Fallon said.

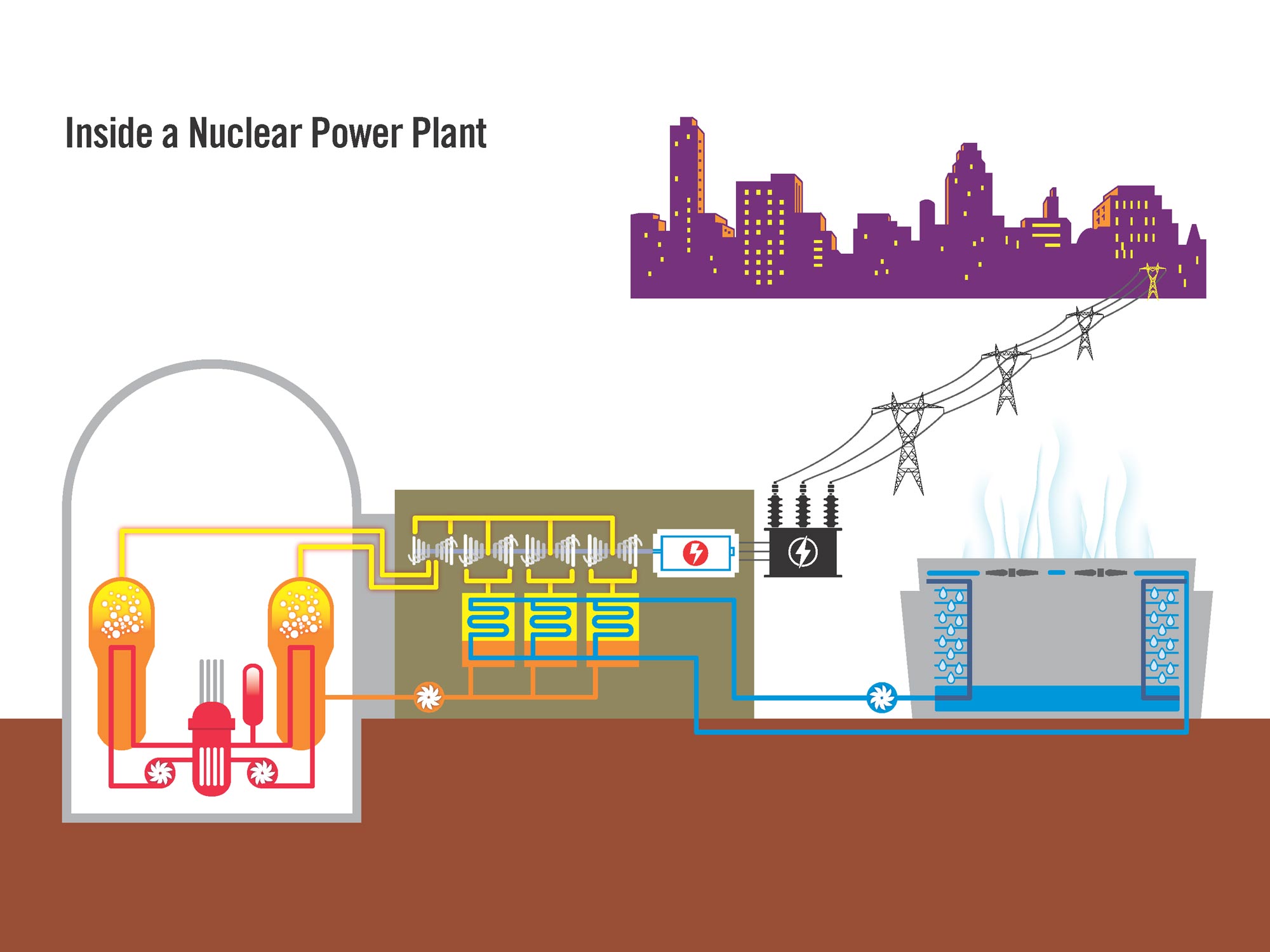

Beyond the source of their heat – binding energy freed from uranium atoms as neutrons break them apart, releasing more neutrons in a chain reaction – nuclear plants work like other steam-based power plants:

“You’re using a heat source to boil water to make steam to turn a turbine to turn a generator to produce electricity.”

VIEW LARGER In a football-field-sized storage facility on the grounds of Palo Verde, 144 20-foot tall concrete casks contain the nuclear generating station’s spent fuel rods. The casks require no power, but are monitored continuously.

VIEW LARGER In a football-field-sized storage facility on the grounds of Palo Verde, 144 20-foot tall concrete casks contain the nuclear generating station’s spent fuel rods. The casks require no power, but are monitored continuously. Palo Verde’s three reactors run full tilt for 18 months. The plant staggers its outages so that two reactors always stay up. Only one-third of a reactor’s 241 fuel assemblies are swapped out per outage. The rest are rearranged to balance the power curve.

This fuel building holds new and spent fuel. The latter cools in a pool for four to seven years before it’s loaded, in groups of 24, into 20-foot concrete casks stored onsite. Within, said nuclear training director Paul Bury, a stainless-steel-and-helium sandwich stops corrosion.

“I don’t need power for a fan or any liquid cooling. Once it’s in that canister, it can sit like that for eternity,” Bury said.

All fuel remains under water, which cools it and helps block radiation. A fuel-handling machine loads fresh assemblies onto a sunken tram, which conveys them to the containment building: a 20-story tower built of steel-lined, reinforced-concrete walls up to four feet thick.

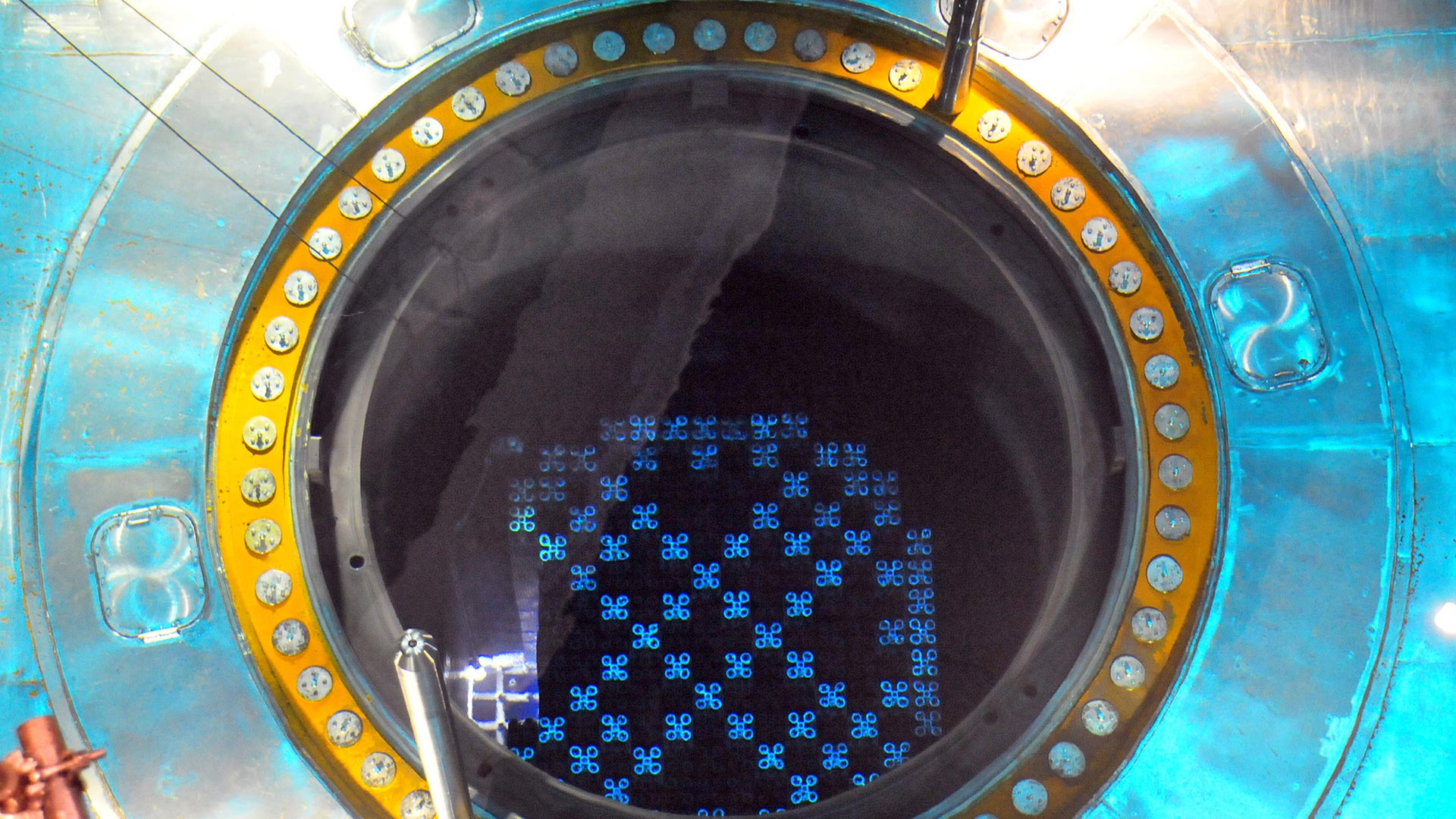

This view of the interior of one of Palo Verde’s reactors reveals the geometry involved in the placement of fuel rods.

This view of the interior of one of Palo Verde’s reactors reveals the geometry involved in the placement of fuel rods.

Inside containment, we stand high above the open reactor. Normally, a pressure vessel head, with control rods to curb reactor activity, would seal the top. Today, nothing stands between us and the radioactive fuel but 20-plus feet of water.

"That’s a ceiling. That’s what’s keeping us right now at a very low dose with that fuel, right there, exposed to us.”

VIEW LARGER A pressurized water reactor uses three loops of water. A closed loop, heated by the nuclear reactor (red), runs through pipes that heat water in adjacent boilers (orange), causing steam (yellow) to spin turbines and produce electricity. This steam is condensed by cooling water (blue) and returns to the boilers. After this heat exchange, this water (blue) flows back out to the cooling towers, where it is pumped to the top and cools as it falls, as droplets, to the bottom.

VIEW LARGER A pressurized water reactor uses three loops of water. A closed loop, heated by the nuclear reactor (red), runs through pipes that heat water in adjacent boilers (orange), causing steam (yellow) to spin turbines and produce electricity. This steam is condensed by cooling water (blue) and returns to the boilers. After this heat exchange, this water (blue) flows back out to the cooling towers, where it is pumped to the top and cools as it falls, as droplets, to the bottom. Palo Verde uses pressurized water reactors. As any egg-boiling Denver resident knows, pressure changes water’s boiling point. Here, pressure topping 2,200 pounds per square inch keeps reactor water from boiling, even at 600 degrees Fahrenheit. Instead, this heat passes through pipes into external boilers.

Nuclear plants provide one of the least deadly forms of energy, yet we can’t seem to shake our fear of fission. We’re haunted by Chernobyl, and we still lack good solutions for nuclear waste.

And that’s a problem, because nuclear power offers the only existing carbon-free technology that can meet future energy needs.

“Even though it’s 20 percent of all the power that’s produced in our country, it provides 63 percent of all the carbon-free electricity,” said Jack Cadogan, senior vice president for site operations.

There’s no plan to expand Palo Verde, but the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has extended its license to the mid-2040s, with an optional 20-year extension.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.